Wreck and Reference might not like you, but they have chosen to stimulate you. After months of sample-editing and meticulous arrangement in their respective home studio bunkers, the duo of Felix Skinner (Los Angeles) and Ignat Frege (Sacramento) followed up their cult-beloved Y̶o̶u̶t̶h̶ LP with a full-length entitled Want. The album encapsulates their assaulting amalgam of vocal shrieks, noise manipulation, and live percussion into a blackened little lozenge more likely to catch in listeners’ throats on the way down than alleviate their ills. In performance, W&R reproduce their wide palette of corrupted found-audio by way of Skinner’s MPC and Frege’s drum kit, spewing forth snippets of choral glossolalia and preset string voices alongside synth pads and nimble tom fills. The sum total, with its miniature sound sources compiled into layered compositions, represents a striking strain of performative musique concrète, filtered through the lenses that have shaped the duo’s musical upbringing: metal’s aggression; DIY basement noise/drone’s tonal experimentalism; solo laptop electronica’s attention to production detail, and pop music’s ironclad structures and expectations.

Now, in the wake of Want’s release from captivity, Wreck and Reference give us a peek under the hood of the creative process that shaped the album in the form of Spill/Fill — a compilation of 75 samples that appear in some incarnation in the album’s final cut. Despite the near impossibility of identifying their locations in the proper compositions, listening through the samples proves to be rewarding in its own right as something like an archaeological exercise. More legible entries like “Guitar,” “Harp,” and “Gregorian,” sit alongside disfigured swathes of static and nearly inaudible murmuring, while titles like “Kanye1” and “Fishbowl 666” leave us with more questions than answers. Having scattered these fragments at our feet, Wreck and Reference don’t seek to elucidate their meaning, but rather invite us to share their own (curiosity) [disgust] {love} in the moments of discovery that prefaced their collaging.

TMT talked to the duo via email about recycling, pessimism, and the power of pop.

Your decision to release the samples that populate Want as stand-alone files differs from similar stem releases by the likes of Trent Reznor and Death Grips, which encouraged crowd-sourced reinterpolations of their original tracks. What compelled you guys to take on this release?

Felix Skinner: Our motivations for this [sample] project were in combination sadistic, sarcastic, capitalistic, and absurd. The internet is a toilet bowl of infinite diameter that is somehow always overflowing with waste. We binge and purge and binge and purge flecks of digital excrement by the bucketload, often doing so just trying to forget how sick the whole cycle is making us. We wanted to contribute to the filth, but do so in a spiteful and withholding manner, cropping tracks unhelpfully short and presenting them in a discourteous format. Although there’s more than enough here to work with, I have little expectation of anything of value being made from these samples (although I would be excited to see someone challenge that assertion). Above all that, however, I just never want to be like Trent Reznor.

Ignat Frege: I liked the idea of releasing something that can’t be “reinterpolated” into a track that sounds similar to the one we made. I wanted people to have something more raw, to encounter a sound that we might have encountered before we started working on a song. So yeah, a glimpse.

How and when did Want come into focus as a full-length album? Can you tell us about the recording process?

FS: We generally write our songs independently, whittling away at them in secret until they reach a semblance of shareable decency and completeness. When we feel brave or drunk, we then put them in a Dropbox folder and send them through the collaborative ringer. We live in very different cities, and channeling 18-odd months of personal experience into two sets of songs set us up to have a very disjointed album. Although consistencies in vocals, drums, and instrumentals (recorded by us) and mixing and mastering (done with the help of Jack Shirley) helped glue the album together sonically, it was almost uncanny how much our songs converged thematically/emotionally. I suppose a sick mind in any land finds itself tangled up in the same inevitable indignities. The name ‘Want’ came about only after the album was finalized. It somehow neatly tied together whatever it was we were tied up in during the writing of the album.

The album cover provokes a visceral reaction. How did the photo come together?

IF: We based the cover around the idea of false goods. A happy acceptance of a covert poison: a hand is pouring a glass of sand and another hand is receiving the glass. It’s tied to the album title and themes, inspired by the ideological and bodily indulgence in things that do not nourish. The desire is ironic and borders on the absurd. Can you think of something that falls into that category?

I’m interested in the motivating factors that led you two into such depths of abstraction, in terms of the tones and samples you feature, especially in relation to your relative position on the outskirts of “metal.”

IF: I dug YouTube pretty deep for some of those samples. I like to soak up something new and build songs out of that. I don’t consider metal; I build songs until they feel right. Metal represents something visceral but it’s drowned by cliches. Metal is easily one of the most un-innovative genres of popular music. For that reason I generally don’t enjoy it, but I do appreciate and can relate to the emotions it tries to present. I guess you would call it ‘convergence with’ more than ‘evolution from’ metal, though we have listened to a good deal of metal. It’s not all awful, as is the case with most things.

FS: The promise and the peril of writing music on a computer is its almost paralyzing limitlessness. I probably go through a hundred permutations of each sound until it sounds right and right is always just a feeling I will change my mind about later. Oh, to plug in an “axe,” crank up the knobs and just “play”! Alas, plumbing the “depths of abstraction” is exactly the thankless tedium I crave. But is it really that perverse a pleasure to want to create something out of novel and unpredictable tools, no matter how clumsy and unpredictable they may be?

I feel most compelled to write music when I feel ostracized and misanthropic.

Conversely, what draws you toward the use of traditional song structures and instances of pop-like chorus/verse recursion within a given composition? Are there any projects within the “pop” sphere that inspire you along these lines?

IF: Song structure just like anything else is something to be experimented with. I love that people hate (or love) verse-choruses, as if their categorical inclusion or exclusion means anything. The pop structure has a function, an emotion it can carry, and for that it can be used as a creative and experimental tool. Recently I’ve gotten into this band HTRK. I really appreciate their subtle pop, and the band name, too. We have probably listened to a lot of what some people would call pop music, but they don’t got no awards for that.

FS: Pop is power. A skull-splinteringly-meaty-riff-laden-breakdown only terrifies the uninitiated. The same goes for any tabletop-feedback-bathing-contact-mic-humping-experimentally-oscillating-noise-droner. Noise/metal/harsh/extreme music can twist up a few neurons at first exposure, but then each repeat exposure only sets off a tiny circuit that I’m pretty sure resides on the other side of your brain from all your feelings. (Obviously, obviously, there are innumerable exceptions to this flagrant over-generalization). Any genuine anxiety or emotional heft these styles may trigger at first gets cut out of the circuit with efficiency as the brain copes with their purported extremity. Pop, however, has been with all of us since birth. Unless you were raised in a cage in some industrial warehouse orphanage, pop (as I define it) is the harmonies, structures, and chord changes that, whether we like it or not, are inextricably stuck to almost all of our memories and emotions. The ability to manipulate that, to reach inside another person and scratch at their foundations, that is a terror you can trigger again and again. It’s almost shocking how underutilized “pop” is in music that tries to be affecting.

RE: “Pop sphere” artists I’ve been recently admiring from afar: Arthur Russell, Sophie, HTDW, Vic Chesnutt, Sun Kil Moon…

I agree with your analysis of pop’s universality — but I’m curious about the idea of noise’s affecting qualities getting “cut out of the circuit” with more listener familiarity. I find noise has the opposite effect on me: Divorced from considerations of “extremity,” noise continues to fascinate me as I become more familiar with its vocabulary over the years.

FS: I think what you’re talking about is something closer to expertise, the thrilling sensation you get when you can discriminate with finesse what you could not tease apart before. I’m always amazed (and personally embarrassed) by how inventive and often superior the devices and approaches others take to creating sound is, and nowhere is that more abundant than in the noise community. I value craft and novelty a great deal, especially being able to compare and relate it to my own processes. It’s also invigorating to immerse yourself in a scene, meet interesting people with similar interests, and develop absurd vocabularies and indices of quality and character that you can only use with other qualified members of your niche. These are all rewarding things to acquire, but I think what they accomplish is not the same as being overwhelmed and consumed by a sound or a song. What you said (and I tried to interpret) about immersion in the noise community could be said about any music or art “scene.” You get obsessed with an idea and you learn everything about it and you learn the language and the landscape and you get emotionally invested in that social identity and community and that whole experience is one of the few things actually worth living for. But, because this is a relatively universal experience, I think you have to divorce those aspects from judging the influence or success of a piece of music. It shouldn’t be surprising, that if you look across all the “scenes” you can think of, you’ll find that the bands that really float [to] the top, the ones that seem to touch something in the most people, seem to be the ones who slyly sneak in pop structures and harmonies into their work. There are a few iconic exceptions, but really very few.

Bringing things back to the ridiculous notion of “extremity” and the point I was trying to make earlier, I think there’s a misconception that many artists have that an audience will perceive their art the way a novice would, or the way they do as a performer. Many seem to think… simply being heavy/intense/extreme/weird/etc. will suffice in affecting their audience. And yes, it’s a rule to not care about the audience, BUT, most of the time those cheap tricks are embarrassing and ineffectual. I don’t think there is one true universal “pop” (the structures/harmonies/rhythms/etc. most of us have been thinking about here are probably all just Western structures/harmonies/rhythms/etc.), but I think there is something powerful about taking stock of what “pop” is in your context, and using it judiciously in your art as a way to tap into something that is fundamental and inescapable.

The Flenser has established a roster of projects that tread the line between what could be loosely categorized as “doom,” and warped pop or rock music (you guys, Planning For Burial, Have A Nice Life). Can you tell us a little about your relationship with the label?

IF: Our relationship with The Flenser has been nothing but amazing. He lets us do whatever we want and works hard to make sure we get it. The catalogue is one of our favorites. I think there has been a unique progression in it and I hope future releases challenge The Flenser as much as they ought to challenge the listeners and everyone’s identities.

FS: Seconded. 2014 is The Flenser’s year.

What you said (and I tried to interpret) about immersion in the noise community could be said about any music or art “scene.” You get obsessed with an idea and you learn everything about it… and that whole experience is one of the few things actually worth living for. But, because this is a relatively universal experience, I think you have to divorce those aspects from judging the influence or success of a piece of music.

Whatever the emotions and intention behind your albums’ misanthropic imagery, song titles, lyrics, and atmospheres may be as creators, I’ve never felt personally alienated as a listener. Quite the opposite: I’m morbidly fascinated and lured in closer by these extreme elements. I’d love to hear your thoughts on the relationship between alienating one’s listenership and inviting them in.

IF: I feel most compelled to write music when I feel ostracized and misanthropic. It’s easy to be motivated by those feelings — helplessness, or whatever — to reassert control over your life. A tiny revenge against the presence of others. I don’t like to write music that much when I’m feeling positive, or maybe I don’t know how to make positive music. Still, the truth remains that things are solid blocks of morally neutral, sour-smelling shit, and none of it matters anyway. We’ll all be swallowed up, to be recycled into durable goods by future generations, and thrown away all over again. In light of that, our attitudes seem pretty reasonable. As far as the listener goes, if they’re on the same page, they will probably get down with this stuff… My only goal is entertaining myself while the world auto-erotically chokes itself with trash.

FS: At least with many of my songs, there was a deliberate effort to be withholding, to draw someone in with an idea or an atmosphere but then prematurely cut them off and leave them dissatisfied and helpless. I’ll admit it’s a petty and spiteful impulse, but that makes it fun, and with the album name and artwork, I thought we gave listeners enough of a warning. Still, some astute reviewers didn’t seem to pick up on this intent and said our withholding and abruptness made them ultimately dislike the album. That felt pretty great.

Does your personal belief in the notion of ourselves being “recycled” into the fodder of future generations thematically tie into your process of recycling samples into your tracks?

IF: What else is there to do except recycle? Can you build from something you do not yet know or have? I don’t think we originally went at this band with the intent to make some grand statement about knowledge or art or whatever; sampling seemed like an interesting way to make music. But statements tend to be inherent and purposes implied. So at the very least, without the ability to divorce those things, I guess we can call the belief in recycling our own. Insofar as you can call anything your own.

FS: The idea of music as a commodity or intellectual property or any of that garbage makes me sick and should make us all sick. I consumed and discharged that which came before me and those who come after will do the same. I mean, seriously, what did you lose that you cry about? What did you bring with you, which you think you have lost? What did you produce, which you think got destroyed? You did not bring anything — whatever you have, you received from here. Whatever you have given, you have given only here (thanklessly and without remuneration). Whatever you took, you took from other people or the planet (without payment or thanks).

What types of situations spark the feelings of ostracism that you channel into these compositions?

IF: There is definitely something that places us on the slope leading into pessimism or depression. I can think of a handful of things that probably took me there, more so from my childhood than anything happening right now. Youth was inspired by those events but I’m not sure how much Want deals with them directly. In my interpretation, Want was written by people who were exposed to certain experiences and from them lacked the ability to cope well, never learning to love. Want deals with purposelessness, not being able to identify with your surroundings, not really having what “normal” people have but not being sure if being “normal” would solve anything, and all the while making terrible bodily decisions. The Want cover alludes to some of the decisions. These deprivations are definitely a result of what has passed, but it’s getting better.

FS: Personally, a big source of angst comes from just asking this question to myself (i.e. goth insecurity). It’s a struggle to not feel entitled to happiness, to balance abject misery/anxiety with the knowledge that so many others face similar existential frustrations piled atop genuine existential threats. Our exploration of hard determinism and self-destruction were certainly ways of coping with that, but I’ve come to recognize that those are ultimately unsatisfying pursuits. Isolation, meaninglessness, and death: but a few of the myriad depressing but objective realities that we can dress ourselves up in with the defense of our empirical understanding. The reward for doing so, however, is elusive and likely nonexistent. So why we are still such miserable bastards? I don’t know.

What compels so many listeners/fans/haters to dissect and overanalyze the genre of a given project to the point of exhaustion? Have you guys experienced these sorts of hang-ups when it comes to categorization of your sound?

IF: Dude, who cares what people can or can’t roll with? Step one, do what you like. Step two, fuck the rest. If someone likes it, I’m all the more satisfied, especially if that allows us to get out of our respective daily lives for a show or tour, but if not, I’m not going to abandon myself.

Plumbing the ‘depths of abstraction’ is exactly the thankless tedium I crave. But is it really that perverse a pleasure to want to create something out of novel and unpredictable tools, no matter how clumsy and unpredictable they may be?

FS: For some reason a lot of people really like talking (arguing) ((having a pissing contest)) about music. Genres let people flex at imaginary challengers. Being the delineator of boundaries allows people to feel like authorities, to feel “true” (-ly the biggest nerd). But like Ignat said, it’s a harmless hobby (I, along with many I love, am guilty of wasting time on it), and not one we have ever tripped over.

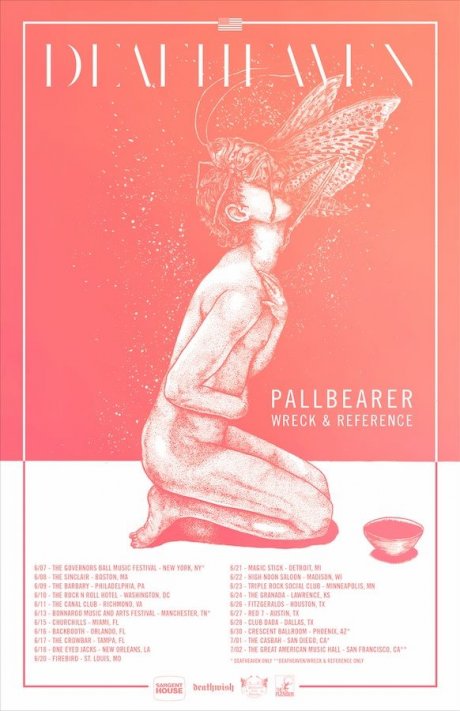

What were some takeaways from the tour with Deafheaven and Pallbearer? Did your sets generally go over well with the crowds that these bands attract?

IF: That was a really fun tour and I am extremely thankful that Deafheaven invited us. It was a unique experience. There was a somewhat expected polarization between diehard Pallbearer fans and Deafheaven fans but I think we fit well on the spectrum. If there were a few people at every show that didn’t like Deafheaven or Pallbearer, there were many more that were left confused by what we were up to.

FS: I have nothing but gratitude for all involved. Whatever the crowds thought on any given night did not impact the fact that those bands are stocked with only good people who taught me an irreplaceable amount.

More about: Wreck and Reference