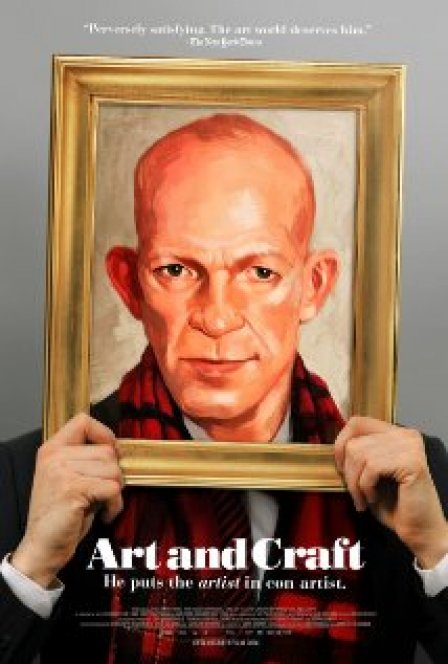

Mark Landis is an imitator of artwork, a world-class illusionist, and an individual with an essence David Lynch could only attempt to capture. Art and Craft, a documentary film by Sam Cullman, Jennifer Grausman, and Mark Becker, is an exploration of Landis’ personal saga as well as the repercussions of and response to his actions within the art world. He is a charming and engaging subject, trapped in the crosshairs of the ethical tenets of the contemporary art world. The film succeeds in portraying Landis holistically, without succumbing to antagonism and bias in the face of his blatant forgeries.

Landis has assembled a veritable Rolodex of artistic eras going centuries back and the strategies and tools with which to imitate them. He is extremely proficient in the materials he works with (unique to each artist), ranging from Milton Avery to Mary Cassatt to Maynard Dixon to the Charles Schultz Peanuts oeuvre. Upon fabricating paintings and objects, he approaches museums and galleries, oftentimes in disguise as a priest (Father Arthur Scott), and presents them as gifts/bequests under the pretense that they belonged to his deceased sister Emily. His forgeries — which are not illegal, since no profit is incurred — have canoodled their way into 46 major institutions and, in many cases, with multiple paintings in different museums.

Matt Leininger, former registrar of the Oklahoma City Museum, was the first to detect Landis’ forgeries in 2008. This resulted in an incensed, morally-driven pursuit of Landis to incite atonement for the deceit at hand. Leininger feels even more individually responsible for exacting justice, since Landis’ actions are not punishable by law. There’s enough to suggest that Leininger’s pathological obsession with Landis has cost him his job (it’s extremely telling that almost all of the content on his LinkedIn profile to date is Landis-related).

Landis is well aware of Leininger’s crusade, yet remains brash and declarative in his actions. He is neither fumbling nor desperate, nor does he fit any description of classic sociopathy. Throughout the film, he appears to be in a comatose and narcoleptic lull, communicating in a feverish rasp and squirrelly laughter. He relishes his role as the lone wolf in the existence he has masterfully curated, paralyzed in a state of profound grief over the deaths of his parents (his house is a cabinet of curiosities in which he keeps them both alive). Earlier in his life, Landis was diagnosed as schizophrenic but is fiercely resistant to the idea of being classified as a “mental patient,” and he exerts command through his artwork.

The documentary captures his environment well; it’s apparent how the Southern Gothic quaintness of Laurel, Mississippi is an incubator for his creative impetus. The atmosphere is colored by the film noir soundtracks coming from his beloved television set, miscellaneous art materials (instruments of war, obtained at WalMart), and masses of bric-a-brac (much of which is related to the memory of his parents). Without a perpetual state of endearing disarray, his creative process and being wouldn’t be the same.

When the University of Cincinnati presents a retrospective exhibition of Landis’ work, Leininger (who contributed to the show) is presented with the opportunity to “confront” Landis. Their resolution is civil, yet lukewarm; it’s apparent that the ideological indignation Leininger feels toward Landis is rather futile. Landis will never yield to anyone, let alone Leininger, who seems to retreat in submission.

At the opening, Landis is asked repeatedly as to why he doesn’t create his own original works in spite of his talent. But it’s clear that these individuals haven’t grasped the full, abstract scope: Landis’ execution of forgeries, his sheer ballsiness to shop them around on a large scale, and his aphorisms and rationale are all in and of themselves performative (and original) questions about notions of facsimile, authenticity, and perception. He is artfully stealthy in his actions and expressions, coyly swilling wine contained in a cough syrup bottle and casually quoting Bela Lugosi; he mirrors the pastiche of the film noir he so passionately devoirs. Mark Landis is described as the the world’s most prolific art forger, but he’s actually much more than that. He asks “where would the church be if St. Peter hadn’t lied?” However cheekily his question is asked, Art and Craft points to poignant questions about replication in contemporary art and, on an individual level, a re-examination of how creatively we live our lives.