Hannes (Darri Ingolfsson), a hero-cop’s son who flunked out of special forces training, successfully applies to internal affairs, and soon learns from a jailed informer that one of his superiors, Margeir, (Sigurður Sigurjónsson) is in cahoots with a drug lord. As the pure-minded rookie recruits allies to his cause and goes after Margeir, alliances shift, crosses are doubled, and Hannes’s family is put in danger.

The end.

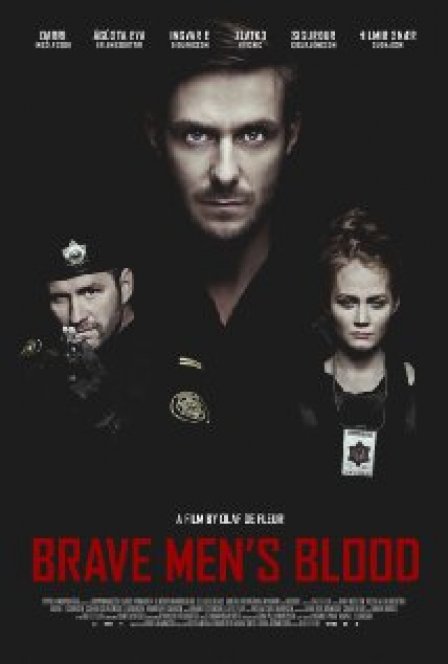

…Unless you want those boilerplate plot points presented with cookie-cutter genre mechanics and a dollop of violence. In which case, by all means, seek out and watch Brave Men’s Blood, but don’t expect anything more to it or its characters than that. Like The Raid 2: Berendal, Brave Men’s Blood is a crime saga sequel that is curiously uninterested in the people in it. That is, it’s much more interested in striking a cool posture than it is in giving its genre trappings actual heft or meaning. There are clear influences underpinning the screenplay here (undercover crime drama twins The Departed and Infernal Affairs chief among them), but in spite of its cursing and violence, its closest resemblance is to any number of network cop dramas. For director and co-writer Olaf de Fleur Johannesson, the crime genre is, here at least, an excuse to have people yell, hit each other with baseball bats, or threaten each other’s kneecaps — to showcase stylish suffering.

Brave Men’s Blood shares a few characters with the series’ first installment, City State, but it’s almost totally disinterested in them or anyone else as people. Personalities and inner lives are subsumed by the film’s blinkered aim of creating Dramatic Crime Movie Conflicts. Even Hannes’s inferiority complex, established early but never capitalized on, is hard-boiled away to a by-the-book cop who through choice and circumstance moves into a moral gray area. Even that arc is only suggested by the plotting; neither the writing nor Ingolfsson’s performance capture how Hannes makes these choices or reacts to his ethical downfall.

More than anywhere else, Johannesson gives away the game when tasked with directing dialogue. His coverage of scenes is filled with handheld angles and movements that have no further motivation than to give the drama empty punch-ups and call attention to their own stylizations (best example: the pretentious short-sided shots, where a character stares at the closest edge of the frame instead of looking across it). There is so little imagination in these visuals: the palette is a dour and uniform blue with occasional spots of orange, and the lighting is merely imitative of Hollywood “production value,” polished, inexpressive, and uninteresting. Movies that look like this have no further justification to their aesthetic methodology than “make it gritty,” and the discombobulations of these shots when cut together — Johannesson, tellingly, is his own editor — betray a lack of engagement with the human beings purportedly shown on-screen. That makes the film’s action and suspense set pieces impossible to enjoy, especially one double-cross scene that starts with a boneheaded “come with me into the empty warehouse” routine and finishes with a gruesome, sadistic splatter.

After Brave Men’s Blood has wound its way through its hall of cliches and uninspired twists, it does come to a more-or-less clearly stated worldview: people are all corrupt, evil is inevitable, all that is good exists because it is useful to all that is bad. It’s a lazy ideology to hang a crime drama off of in the first place, yet it’s dispassionately evoked with a few lines of tossed-off voiceover. It’s not a surprise that it would bid farewell to its skin-shells with a shrug.