I often categorize films that I appreciate on a highly subjective scale that can be fairly summed up as: “Would I tell Person X this is mandatory viewing?” My recommendations, as yours may be, generally depend on what I think a particular person would enjoy or find relatable, especially if he or she wouldn’t otherwise be aware of it. In the case of Matt Porterfield’s stunning Putty Hill (TMT Review), I made a friend sit down and watch it with me for the second time because she has an abiding affection for Baltimore. While this may be somewhat self-serving, I feel like I succeeded in sharing what I believe to be a fine piece of truth-bearing cinema. So for this one, the director’s follow up, the bar was high, as was my anticipation.

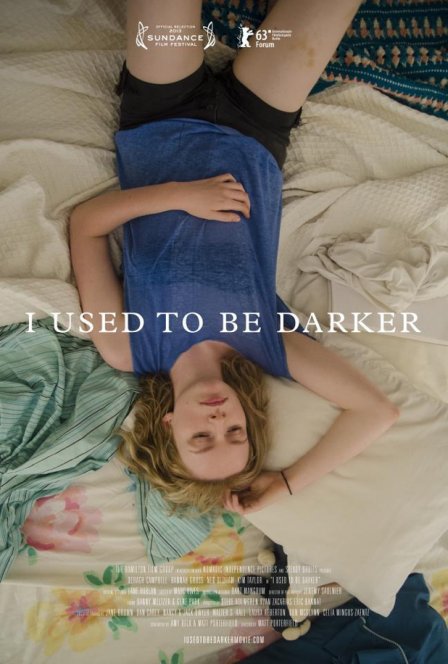

In Putty Hill, Porterfield shed light on the soul of a community through the connections of a fractured extended family, culminating in a heartrending rendition of “I Will Always Love You” — performed by a young Sky Ferreira, who has since catapulted to stardom. With I Used to Be Darker, the director narrows his scope but retains the focus on familial discord. At the center of the film is Taryn (Deragh Campbell), a girl on the verge of adulthood who has fled Northern Ireland and landed in Ocean City, Maryland. For reasons only alluded to, she abandons the seaside and makes a despondent call from a bus station in Baltimore, where she is picked up by her uncle (Ned Oldham as Bill) and taken in as a refugee. Though the nature of their relationship is initially unclear, Porterfield gradually unveils the circumstances and introduces us to her cousin Abby (Hannah Gross) and aunt Kim (Kim Taylor). Unbeknownst to Taryn, Bill and Kim are in the process of dividing their possessions, and Abby has distanced herself from her mother for being the cause of the split.

Between the dismantling of her aunt and uncle’s house and the concealed reasons for leaving her homeland, Taryn has become a damaged adoptee and runaway orphan. This analogy is further expressed by the sibling-like tension with Abby, who is on break from college and has a bad case of disgruntled daughter syndrome. As they are wont to do, Porterfield’s characters float through the sketch of a story, lazing by the swimming pool and slinking through a sludgy punk show (featuring Drag City’s Dope Body) that feels genuine and alive. The director nurses the slow-build with exquisite fluency, showing us reserved emotions that erupt out of nowhere and shatter the morning. When Abby lashes out at her mother, she is acting as we would expect an angsty teen to, but a tirade directed towards Taryn reveals her unpredictability and heightens the power. Her cuckolded father, meanwhile, holds it in with whiskey and jams in the basement before exploding.

Porterfield has used non-actors before and yielded excellent results. With Darker, he goes one step further and employs unrecognizable musicians as leads. Bill’s spiraling sadness is fully exposed as he sings a dirge in the basement, the voice of Bonnie “Prince” Billy whispering across the room. It may seem like an overdub, but Ned Oldham is in fact the older brother of said artist (nee Will Oldham), and they have recorded together professionally since the Palace projects. Kim Taylor is another rootsy songwriter I was unfamiliar with, but she too has been a solo artist for more than a decade and her music has soundtracked several television shows (most notably ones on the dearly departed/reviled WB channel). These two faithfully draw out their characters’ histories as wearied balladeers, and in foregrounding their talents Porterfield and co-writer Amy Belk keenly underscore the torment of a terminal marriage. The outcome is an authentic and unfettered portrayal of divorce.

Compliments aside, there is something clearly missing in Darker, a hole where that ineffable resonance we yearn for could be. The pieces are in their respective places, yet the effects are softer, less immediate. This is a demonstrably cleaner effort than Porterfield’s previous outing, and that polish may be the culprit. So I Used to Be Darker doesn’t quite make the cut for the mandatory viewing list, but it does prove to be a worthy addition to his flourishing résumé.