Earlier this year, I went to the Passenger Bar, a dimly lit and lovingly arrayed watering hole in Williamsburg, to see the first show in a month-long residency by Cinema Cinema. Their guitarist and singer Ev Gold and I had made each other’s acquaintance a few years prior, when my band and his shared a bill at the Lower East Side’s now-shuttered Local 269; we’d discovered a mutual enthusiasm for film, pedalboards, and the pummeling musical nexus of free-jazz and industrial noise. Cinema Cinema was now merging those three loves in a series of shows during which they and a succession of guest musicians improvised live scores to classic films. That night’s film was Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Santa Sangre and the guest was Martin Bisi, the legendary proprietor of Gowanus recording studio BC Studio and subject of Ryan Douglass and Sara Leavitt’s new documentary Sound and Chaos: The Story of BC Studio.

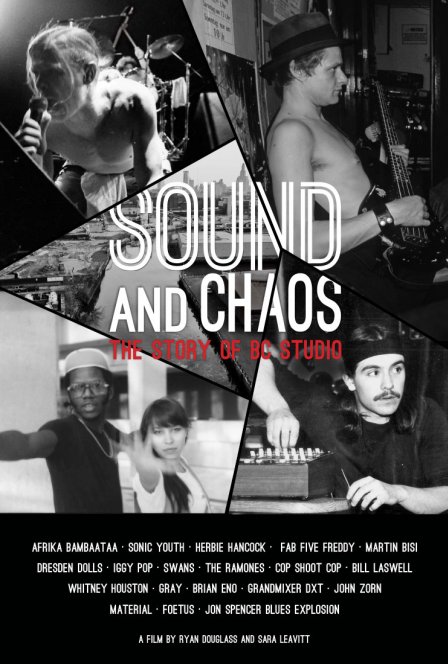

Bisi arrived, nonchalantly unpacked and set up his gear, donned a long black cloak, and transformed from an unassuming working-class musician into a wild sonic shaman, coaxing beautiful, strange, and sometimes discordant sounds from his guitar and voice. This dichotomy of modesty and greatness is characteristic of both Bisi and his cavernous studio, wherein he has recorded iconic works by such luminaries as Sonic Youth, Swans, The Dresden Dolls, Lydia Lunch, John Zorn, Afrika Bambaataa, Foetus, Cop Shoot Cop, Ginger Baker, and Herbie Hancock. Starting with Bisi’s relationship with Material cohort Bill Laswell and the generous patronage of Brian Eno (who wrote the check that paid for the studio), Douglass and Leavitt chart the history of BC Studio from its humble hip-hop beginnings through its halcyon days as the unofficial home of New York No Wave, noise, industrial, and alternative throughout the 80s and 90s.

Bisi is an effusive host, taking bemused pride in the unorthodox quirks of both his studio and his method. “I like being a part of things and people doing stuff,” he avows with some degree of understatement, showing off his vintage mixing console and analog delay units with the same enthusiasm as the burn marks on his floor, which were souvenirs from a raucous session with Sonic Youth during which Thurston Moore threw a lit string of firecrackers into the vocal booth where Lee Ranaldo was recording. (The ensuing explosions can be heard quite clearly on the Evol track “In the Kingdom #19”.) Recording enthusiasts in particular will enjoy hearing Bisi expound on his recording methods in both practical and philosophical terms, as he explains his thoughts on acoustical space, how to mic drums, and what makes a good producer.

Perhaps the documentary’s greatest strength, however, is its abundance of interviews with the artists whom Bisi has recorded. Legendary figures of the New York underground such as Michael Gira (Swans, Angels of Light), Jim Coleman (Cop Shoot Cop), Bob Bert (Sonic Youth), and JG Thirwell (Foetus) share engrossing tales of life in Bisi’s studio (the top floor of which doubles as his apartment). By illuminating Bisi’s unique brand of controlled madness, the interviews shed light on the creative process and the role of environment in the creation of art. From this springboard, Douglass and Leavitt zoom out to the recent history of Gowanus in general and to the opening of a local Whole Foods in particular to spotlight the neighborhood’s ongoing gentrification and its subsequent effect on the arts communities, which had over previous decades come to define the area. Rather than becoming morose or backward-facing, however, Douglass and Leavitt point their cameras toward younger groups such as Pop. 1280, Rude Mechanical Orchestra, and the aforementioned Cinema Cinema who continue to flock toward BC Studio, inspired by Bisi’s progressivism and legacy in equal measure.

Filmmaker Michael Holman, who formed the Bisi-produced band Gray with Vincent Gallo and Jean-Michel Basquiat, explains early in the film that Afrika Bambaataa used his influence to leverage a truce among several New York gangs — why fight when you can party? The music Bambaataa created at BC Studio like “Zulu Groove” became the soundtrack to that party, and the open, inclusive spirit in which it was birthed lives on. At a brisk 71 minutes, Sound and Chaos could certainly stand to be fleshed out a bit with more interviews or in-studio footage. This isn’t a criticism of the film, but rather a plea to the filmmakers; the subjects in Sound and Chaos are so compelling that one can’t help but wish for more stories of their experiences in that cold, dank Gowanus basement, searching for sounds and inspiration, guided and encouraged by one of the unsung heroes of a much-fabled scene.