Biopics are difficult to balance. On the one hand, they must present the audience with enough historical material to give them the feeling they’re learning something about the topic at hand. On the other hand, they must not be overtly didactic or too focused on endless historical facts, so as to not bore the spectator to sleep. Director Cao Hamburger has already proven to be very skilled in the difficult task of working with actual historical material, as revealed by his impressive (and unfortunately rarely watched) HBO series, Filhos do Carnaval (2006), dealing with the shady connections between Rio de Janeiro’s samba schools and the illegal gambling mafia. Likewise, The Year My Parents Went on Vacation, his critically acclaimed 2007 feature film, showed a firm hand in combining the historical setting of a Brazil under military dictatorship, the 1970 World Cup, and the individual drama of a 10-year-old boy.

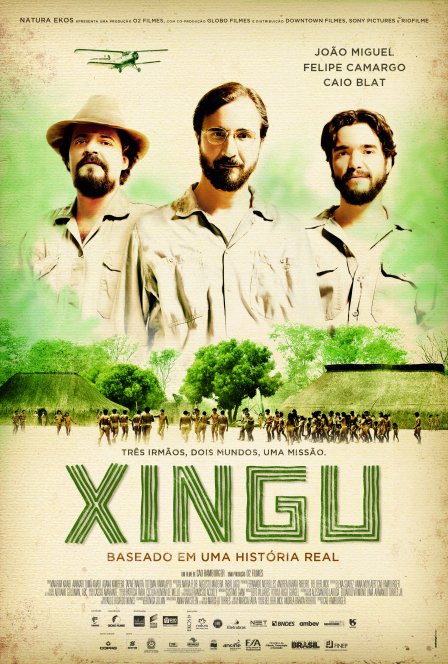

Inspired by the real-life stories of the Villas Boas brothers (Claudio, Orlando, and Leonardo), Xingu begins its tale in the 1940s and spans three decades, from the moment the brothers were still young, middle class idealists until they became some of Brazil’s most important political figures for indigenous rights. Most importantly, the brothers are remembered as the ones responsible for the creation of the Xingu National Park (1961), one of the world’s largest indigenous reservations, but the finer details of how this all took place are not made clear in Hamburger’s film. The brothers begin their journey as members of a military-led expedition in 1943 towards the “inhabited” and unknown west of the country — part of a larger agenda by then-president Getulio Vargas. The film begins with the brothers disguising themselves as poor and uneducated (since the film doesn’t explain this, we can only deduce the expedition did not allow overtly educated members, possibly for fear of insubordination). Apparently youthful and adventurous spirits, all they had in mind at this stage was the prospect of new experiences and adventures in an unknown land. The territory, however, is not truly empty, and the expedition soon comes across several native tribes. Once the three brothers make contact with the indigenous population of the region, they conclude that the only way to avoid the otherwise-inevitable demise of these inhabitants is by the policy of isolation and the prevention of acculturation at all costs — an ideology that, while made to sound rather outdated by Hamburger’s film, still remains dominant in Brazil’s contemporary indigenous policies.

Being no stranger to Brazilian history, I was more than intrigued when former president Jânio Quadros appeared onscreen as one of the Villas Boas’ main supporters in congress, lobbying for their struggle for funding and securing the land for Xingu Park. Having stayed in office a mere seven months before resigning under mysterious circumstances and with no clear ideological agenda (among his policies were the state decoration of Che Guevara, the prohibition of gambling, and outlawing bikinis on public beaches), Jânio Quadros remains one of Brazil’s most emblematic and eccentric political figures. Needless to say, my brain was working overtime trying to figure out why the preservation of indigenous cultures was such a high priority for the former president. This is just one example of how rushed Xingu’s narrative is, often jumping several years in time with no clear political or cultural context. For instance, the only indication that the Villas Boas are, at one point, dealing with the military-led government (from 1964 through 1985, Brazil was under a military dictatorship) is when a high-ranking military officer meets with the brothers to inform them of their plans for building the Transamazonica Highway (one of the military government’s most ambitious plans, as well as one of their most shameful failures). This brings up yet another critical issue: how the Villas Boas gained so much political leverage that a military dictatorship had to practically ask for their authorization (or, at the very least, arrive at a diplomatic agreement) before building a major highway over their indigenous reservation. The actual construction of the Xingu Park raises the same puzzling question. While the Villas Boas brothers were responsible for the planning and the gathering of the natives in the region (whom, regardless of their ancient rivalries, now had to live together — another issue barely touched upon), the actual political effort was the work of Darcy Ribeiro, a politician and anthropologist with prestigious academic and intellectual affiliations who is granted no more than a few seconds of screen time.

In the end, Xingu is a flawed film, but one that has its heart in the right place. The Villas Boas have been unjustly forgotten by history. Even in the several anthropology classes I took during my university years, I rarely heard their names. With a mere running time of 100 minutes, Xingu could have dedicated more screen time to better explaining the political background and cultural environment of the decades it spans. This holds particularly true for a non-Brazilian audience, which I imagine will be far more baffled by trying to understand what on earth is going on. Technically speaking — and in spite of some cheap-looking strategies (the flashing newspapers on the screen, which indicate jumps in time, seem like tacky Photoshop tricks) — Xingu is a more than decent effort. Having been filmed in the actual Xingu National Park, the cinematography by Adriano Goldman is at times breathtaking, and the actors (especially Felipe Camargo as Orlando Villas Boas) do a fine job of overcoming some of the script’s limitations. Xingu is a film I would recommend to anyone, but it might be wise to leave some Wikipedia tabs open while watching.